In the last issue of The RISK Rituals, we reflected on the non-revolution of the Super Bowl crypto ads and noted that when you see a revolution on TV, it’s not likely to be a true revolution.

This week I have a truly remarkable story to share with you of a quieter financial revolution that started 70 years ago this month and that most people know little to nothing about. This revolution was never televised because the people that understood its value didn’t need anyone else to know about it in order to take their new power.

I’m talking about the revolution launched by Harry Markowitz with the publishing of his paper in the March 1952 issue of The Journal of Finance. The paper was titled simply “Portfolio Construction.” William F. Sharpe, author of the now ubiquitous paper The Sharpe Ratio, said of Markowitz and his 1952 paper, “Markowitz came along, and there was light.”

Here are the opening sentences of the revolution:

The process of selecting a portfolio may be divided into two stages. The first stage starts with observation and experience and ends with beliefs about the future performances of available securities. The second stage starts with the relevant beliefs about future performances and ends with the choice of portfolio. This paper is concerned with the second stage.

I’ve talked about Ray Dalio’s holy grail portfolio philosophy many times before in this newsletter. Dalio famously said that the holy grail portfolio is “15 to 20 good, uncorrelated return streams.” Dalio is actually just restating Markowitz: stage 1 = find good opportunities, stage 2 = select a subset of good opportunities that are uncorrelated. Markowitz practically opened and closed the book on stage 2 way back in 1952.

Markowitz called his approach to stage 2 “mean-variance analysis.” In his groundbreaking paper, he argued convincingly that “the investor should consider expected return a desirable thing and variance of return an undesirable thing.” The expected return is the mean return.

The best visualization of Markowitz’s theory that I know of is the “spaghetti plot” that meteorologists use to forecast the possible paths of hurricanes. Here is a spaghetti plot of Hurricane Irma. The greenish lines in the middle of the spaghetti plot are the most likely paths of the forecast. The whiter lines on the edges of the plot are the limits of the possible variances of what paths the hurricane might follow.

This spaghetti plot was made on September 8 when Irma was a category 4 storm approaching Cuba. I lived in Tampa at the time, and it was still two days before the storm was in danger of hitting Tampa. At that time, Tampa wasn’t on one of the green mean lines. The outer variances had the storm path possibly even still out at sea in either the Gulf of Mexico or even the Atlantic. Two days later, on March 10, Irma passed right over my home as a category 2 hurricane.

This is exactly how professional and institutional investors and traders forecast market risks. We’ve certainly had a bird’s-eye view of this process with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. A month ago, all we knew was that Russian troops were amassing along the Ukrainian border, but we didn’t know if it was a strategic bluff or if the current world order was about to be upended.

The mean narrative was that Russia would use its show of force to pressure Ukraine to step back from NATO. Maybe Russia would annex Donetsk and Luhansk like they had done with Crimea. The edges of the variances were: 1) Russian troops would start heading home after their exercises, or 2) Russia would launch a full-scale brutal assault on its neighbor.

What most nonprofessionals don’t understand is that the range of variances matter as much if not more than the mean outcome. The wider the range of possible variances, the greater the risk. The greater the risk, the less likely the achievement of any particular reward path. The more possible paths there are, the less an investor is willing to pay to bet on any particular path being the actual path.

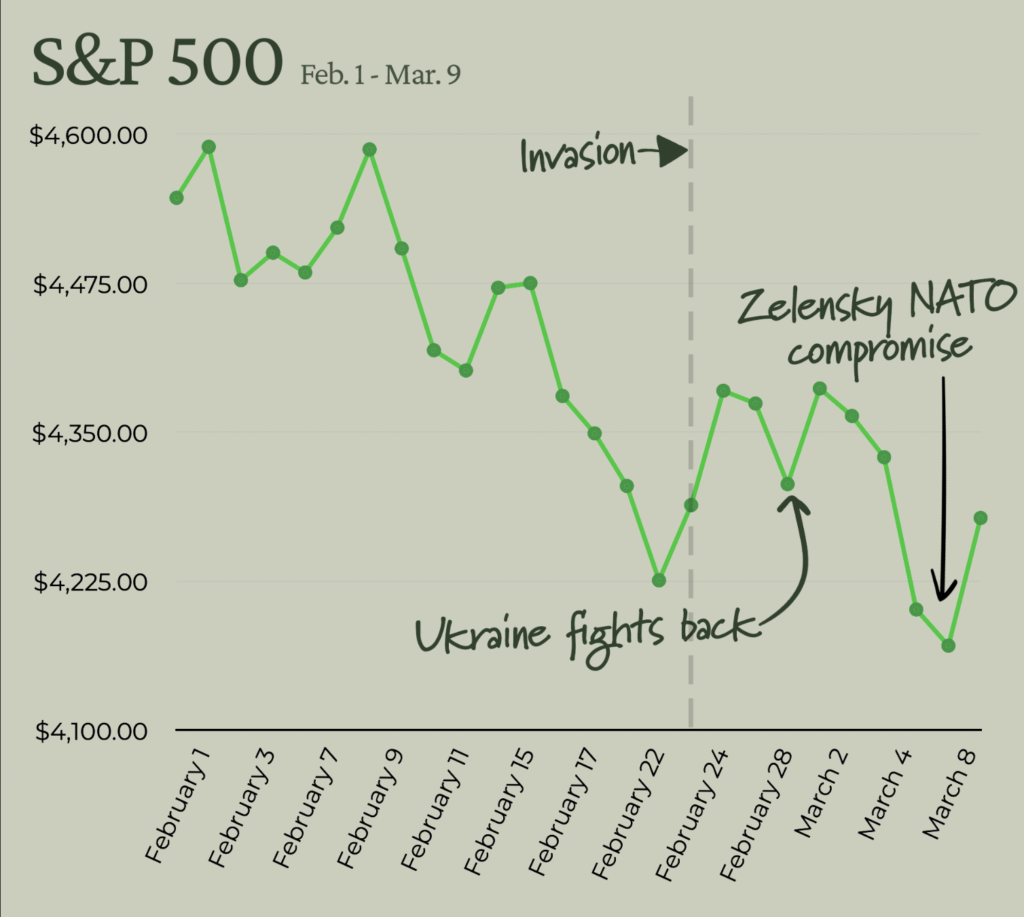

This is how uncertainty impacts prices. As uncertainty increases, prices tend to go down because the range of possible outcomes is expanding. This is exactly what we saw from about February 1 to February 23. No invasion had started yet, but the possible variances were growing (and the mean was shifting more towards an invasion).

Once the invasion began, there was a relief rally as markets started to anticipate that Russia would quickly achieve its objectives and then things would start to stabilize. By March 1, the uncertainties were increasing again as Ukrainian resistance was much stronger than anticipated and the prospect of a quick resolution faded. Most recently, President Zelensky indicated a willingness to compromise on NATO membership for Ukraine, and prices rallied as uncertainty diminished.

This is the genius of Markowitz. Markowitz showed us that variance itself has a cost. As human beings, we are wired to focus on the mean and to not think as much about the possible variances. Thinking about variance doesn’t come naturally. We want answers, not more questions. Markowitz showed that thinking about variance is an absolutely essential component of financial decision making.

We hear in the media all the time that “markets hate uncertainty.” It’s true, in an overly simplistic way, but I would say it differently. I would say that markets process uncertainty. Markowitz showed us that markets respond to uncertainty mathematically – not emotionally.

Of course, individual and crowd emotions color the mathematical response of markets and lead to a constant cycle of overreactions. Yes, those overreactions are where wholesale market makers, hedge funds, and media companies make the big bucks, but the initial underlying market reaction is perfectly sound! Markowitz showed 70 years ago that it is logical, not emotional, to pay less for any one particular possible outcome when the range of possible outcomes expands.

This is why, by the way, I’ve made such a big deal about histograms over the past year. Histograms show us the mean (the middle) and the variance. Pardon me while I indulge in a bit of schadenfreude, as it was just about a year ago that Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev called legendary investor Charlie Munger “disappointing and elitist” because of Munger’s warning against gambling in stocks. Since Tenev’s tantrum, Berkshire Hathaway is UP over 22% while Robinhood is DOWN over 65%.

Why? Because in times of increasing uncertainty, the stability and lack of variance of Charlie Munger and Berkshire Hathaway is valued much more highly than the meme-chasing instability of Vlad Tenev and Robinhood. Their respective one-year histograms tell the whole story.

Most people think that investing is about being right and that those investors who are right make the money. Being right is definitely part of it, but that is only what Markowitz calls stage 1. Stage 2 is about balancing the relationship between risk and reward. I would argue that these days, stage 2 is even more important than stage 1, when it comes to portfolio selection.

Balancing risk and reward is the essence of mature investing, and it’s exactly what markets themselves do during periods of increased uncertainty. It’s a logical response to increased uncertainty.

There are plenty of investors who get very emotional during times like this, but it’s more than likely that they are highly emotional because they didn’t think about risk first and were instead just dreaming of rewards.

Now that risk has inevitably reared its ugly head, those dreams are receding into the distance. For the record, this is exactly what bothered me so much about our would-be Super Bowl advertising revolutionaries – they pitched all reward and no risk. They pandered to the ignorance of their audience.

People can and should get very emotional about the horrors of war, and our consciences should inhibit us from investments and/or trades that might be profiteering from war. We should also do whatever we can outside of the markets to help mitigate these tragedies and relieve the suffering.

As investors, however, we are not in control of world events, and we have to keep doing our job of assessing risks and taking smart ethical risks that are likely to produce reward within an acceptable period of time.

That’s what markets do, and that’s what investors should do, too. It’s high time that more investors learn about this remarkable financial revolution that is as important today as it was 70 years ago.

Happy 70th anniversary to a quiet financial revolution launched by Harry Markowitz. The self-appointed crypto kings would do well to take a knee.