In the Back to the Future movies, there’s a plot line where the big adversary, Biff Tannen, thanks to a time machine, gets his hands on a book that reveals the outcome of every game in every major sport for the next 30 years. You can guess what happens next: He starts betting and winning, betting and winning, over and over again, because he knows what’s going to happen.

This sounds farcical, but there are some big players out there in the markets right now who know more about the future than you and I do, and they didn’t need a magic DeLorean to see it. Robinhood, and now other retail broker-dealers, are selling it to them.

Even more sobering than that, however, is the fact that the “betting on the future” business model being pursued by these big players is increasingly the business model of the entire internet – particularly Web3. By the time we get to the end of this article, you’ll know my dark horse candidate for who will really rule the metaverse.

Before we get to the cautionary tale, we need to define a few terms.

When you want to invest in, say, the Ford Motor Company, most of the time you simply put in an order and buy the stock immediately, at the national best bid offer (NBBO) price that the market has to offer. That’s called a market order.

A limit order, on the other hand, is more complicated. You tell your broker that you want to buy Ford, but only under certain conditions.

A simple example would be if you told your broker, “Buy Ford when it hits $15.” That’s called a marketable limit order (MLO). It’s tied to a specific price point, and as soon as Ford transacts at $15, your limit order immediately becomes a market order – which is why it’s called marketable.

But limit orders come in many forms. You can say, for example, “Sell Ford when it drops 10% below its high-water mark during the period I’ve owned it.” This would be a 10% trailing stop loss order – which is really just a more complicated kind of limit order.

These more complicated types of limit orders are called non-marketable limit orders (NMLO). They take many forms, but because their conditions are all more complicated than just “buy or sell at this price,” they do not immediately convert to market orders once their conditions are met.

Here’s the crucial thing about limit orders – both marketable and non-marketable: There’s a time delay between the moment when you decide to buy or sell and the moment when that transaction takes place. When you place any kind of limit order, you are signaling your intention, but you are not immediately executing that intention.

Whoever can see your limit order also knows your intention and, hence, knows just a little bit more about the potential future of markets. Whoever can gather millions and millions of those limit orders knows a lot more about the potential future of markets.

NMLOs can be extremely useful. I founded my first company back in 2005 to help retail investors use NMLOs to great advantage, but I never, ever disclosed that data to a third party. In fact, I regularly told my subscribers to make sure and not put any orders in the market.

Some brokers do keep this data private. Robinhood emphatically does not. Their entire “free trades” business model is based on selling to wholesale market makers (WMMs) the information about what you’re likely to do in the future. The wholesale market makers can and do use that information to get an edge in the markets – an edge that you don’t enjoy.

Back in 2018, the SEC amended Rule 606 to require more transparency from brokers and market makers about this practice of payment for order flow. Each quarter now, brokers like Robinhood are required to file a report with the SEC detailing what the WMMs paid them and how much.

The full year 2021 data from Robinhood’s 606 filings is now in the books, and we can see exactly how valuable it is to Robinhood to sell their users’ data to WMMs.

In total, Robinhood was paid $965 million in 2021 for selling its users’ data to WMMs. By the way, this is just for equities and equity options. Robinhood isn’t yet required to disclose if/what it gets paid for order flow in cryptocurrencies.

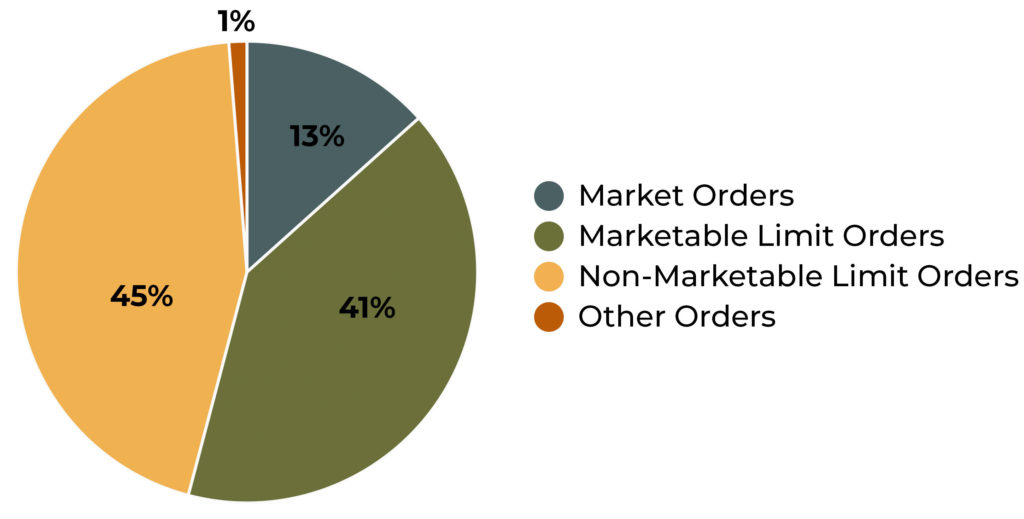

$965 million is shocking enough, but it starts to get particularly interesting when you dig down into the data and see how it breaks down. What’s particularly striking is that $824 million of that was paid for limit orders – both marketable and non-marketable. That’s 85% of the total. Here’s how the order types break down:

I am simply blown away by these numbers. Fully 45% ($431 million) of the payments to Robinhood were for NMLOs. I always knew that it was a bad idea for retail investors to show their hands by putting their orders in the market, but I never imagined that it was $431 million of bad. And that’s just for Robinhood!

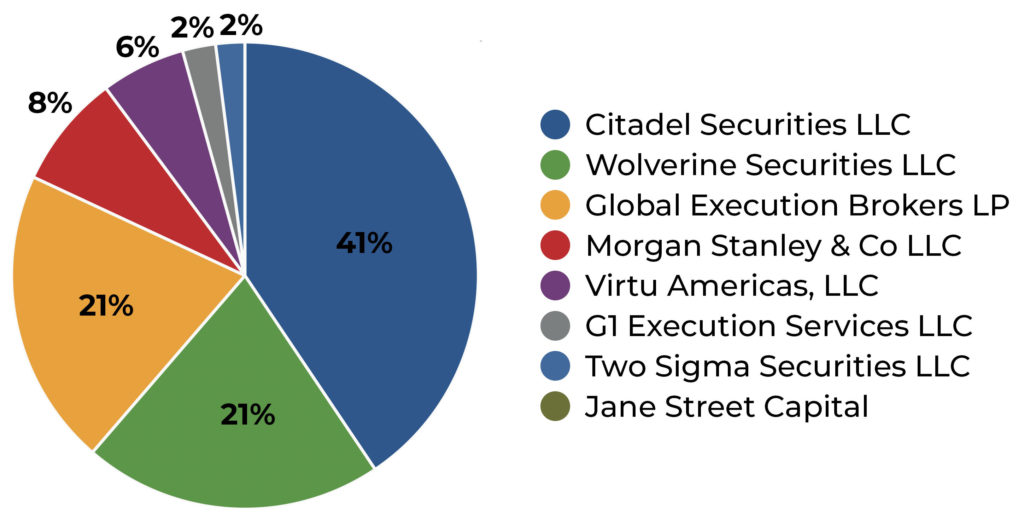

It’s also interesting to look at exactly who these WMMs are. The following pie chart shows all of the WMMs who paid Robinhood for order flow in 2021:

Citadel Securities clearly stands out as the largest consumer of data from Robinhood’s users. In 2021, Citadel Securities paid Robinhood $335 million for order flow. I’d say that it’s time to learn a little bit more about Citadel Securities.

Citadel Securities is the brainchild of Ken Griffin, its current chairman and 80% owner. Ken Griffin is also the founder (back in 1990) of one of the world’s largest and most successful hedge funds, which is now simply called Citadel.

Citadel’s flagship fund is called Wellington, and it’s now worth $43.1 billion. It’s a so-called multistrategy fund that runs a “market-neutral strategy.” Here’s a definition of “market-neutral” from Investopedia:

Statistical arbitrage market-neutral funds use algorithms and quantitative methods to uncover price discrepancies in stocks based on historical data. Then, based on these quantitative results, the managers will place trades on stocks that are likely to revert to their price means.

As it turns out, Wellington was the top performing multistrategy fund in 2021. Per Bloomberg, “Ken Griffin’s Citadel bested its mega-multistrategy peers, posting a 26% return for 2021.”

I don’t know what the rules are about what intelligence Citadel Securities can share with Citadel the hedge fund, but I certainly do know that the NMLO data Citadel Securities buys from Robinhood would give a hedge fund like Wellington a considerable advantage in the markets. (I’ve really tried to figure out if there are restrictions between Citadel and Citadel Securities but I haven’t been able to find anything. If anyone knows, I’d love to better understand.)

What I also know is that both Citadel and Citadel Securities share the mind of Ken Griffin. Whatever the rules are, I just can’t see how no intelligence from Citadel Securities could cross over to Citadel. Frankly, I can’t understand why the SEC even allows this. But that’s a conversation for another day.

I’ve only scratched the surface here as to what’s going on behind the scenes in markets today. Much of the credit for these insights goes to Paul Rowady and his superb Alphacution service. It’s wonky and nerdy stuff, but Paul is truly pulling back the curtain on what goes on behind the scenes in markets, and I’m grateful to him for his work. I had hunches, but Paul did the digging into the data to put the meat on these bones.

If, like me, you’re a little more skittish now about what’s really going on in the markets, I’ve got even more for you to chew on. Citadel Securities just partnered with powerhouse venture capital firms Sequoia and Paradigm for the explicit purpose of extending their reach to new markets, including crypto.

From the press release (emphases are mine):

“The talent of our extraordinary market making team combined with our powerful risk management techniques have transformed the client experience in the many markets we serve,” said Citadel Securities Chairman Ken Griffin.

The second relevant quote is from Matt Huang, Co-Founder and Managing Partner of Paradigm: “We look forward to partnering with the Citadel Securities team as they extend their technology and expertise to even more markets and asset classes, including crypto.”

The internet is financial. I’ve been saying that for a long time now, but recently someone else said it too – and much more eloquently than me. The Atlantic published a piece this week by Ian Bogost entitled The Internet Is Just Investment Banking Now. It is a must read.

In the article Bogost makes the point that the internet has always financialized our lives and that with the fully trackable Web3 version of the internet, that financialization is finally explicit. As he puts it, “Now, at last, the wealth seeking is printed on the tin.” You’ll just have to read the article to get the full picture.

I’m sure by now you can see where I’m going with this. My bet is on Ken Griffin ruling the metaverse over Mark Zuckerberg.

Actually, that’s not true. My bet, as crazy and naive as it may sound, is on you and I ruling the metaverse. That isn’t going to happen, however, unless we start to do a couple of things.

First: Data privacy is key. Nobody should be able to use your decision-making against you. Don’t use a broker that sells your decision-making to any third party, period. These brokers need to know that they cannot have our business if they are going to sell our data. TD Ameritrade has been my broker for over 20 years now, but no more. I’m moving on.

Second: Master risk or fall behind. The data I’m sharing today is just a picture of big-league risk management, on a massive scale. The risk literate are literally taking candy from the risk-illiterate babies. The sooner you realize that risk is the make-or-break tool in your investment strategy, the better.

Start there, and Ken Griffin is going to find it a little harder to peek at your poker hand – both in the markets and in Web3.

P.S. Ken Griffin literally bought the Constitution recently for $43.2 million. I hope he reads it. We all should – especially the first 10 amendments.