In Part 1 of The Day the Internet Died we laid out the case that in a very fundamental way the internet of today was not made to serve us. Since Google decided to monetize its spectacular search technology with AdWords back on October 23, 2000, the internet has been architected for the needs of marketers and advertisers first. We are the product. The advertisers are the paying customers.

Today’s internet is what I like to call Television 2.0. It’s a version of television that the broadcast networks of yore could only have dreamt about. It’s a version of television where content is produced and distributed at lightning speed and then, most importantly, responses are measured in real time. Google and Facebook are more like yesterday’s NBC and CBS than they are like yesterday’s Intel and Microsoft. Google and Facebook may not be producing the content, but they are certainly monetizing it. They are media distribution platforms, fueled by technology and data and monetized via advertising.

It used to be that the broadcast networks had to hire the likes of Nielsen to come and sit in our livings rooms to watch us and see how we responded to media. No more. We’ve invited the “watchers” right into our homes. In fact, we pay extra to allow Alexa and Siri to listen in on us continuously so we can have our consumer desires fulfilled at the speed of sound.

Look – I’m not saying that we don’t get benefits from this advertising-funded version of the internet. We do. What I am saying though is that we don’t fully understand its costs. We don’t understand its architecture. We don’t understand its patterns of profit and loss. Much is intentionally hidden from us behind the façade of “free.” Moreover, if we did better understand its costs, we would be in a better position to capitalize on its authentic benefits while better controlling its costs.

Sound good? I hope so!

So today I am going to show you the pattern that drives online profitability more than any other. To illustrate what this pattern looks like and the role that it plays in the profitability of today’s online platforms, I’m going to keep pulling on the thread of that Trojan Horse of retail investing – Robinhood.

We all know that Robinhood’s IPO is this week. Their new ticker is, appropriately, HOOD. What’s hiding under that HOOD? Let’s take a look.

Robinhood makes money when its users (not its customers) trade actively. Robinhood makes more money when its users trade less liquid securities – i.e., securities where there aren’t a lot of buyers and sellers. Robinhood’s most profitable transaction (as we covered in Part 1) is something like an options trade on GameStop during a meme-driven feeding frenzy. Contrast that with something more like Vanguard’s revenue model of driving down transaction costs through the marketing of low-cost index funds. The different profit models could not be more stark.

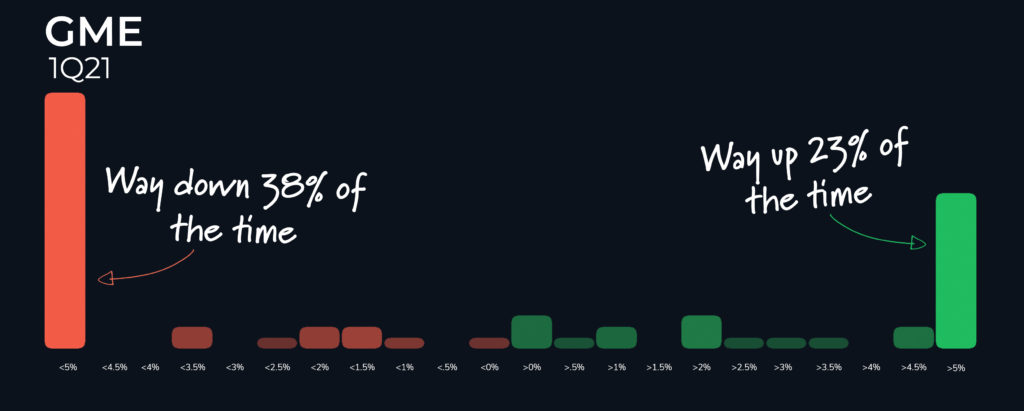

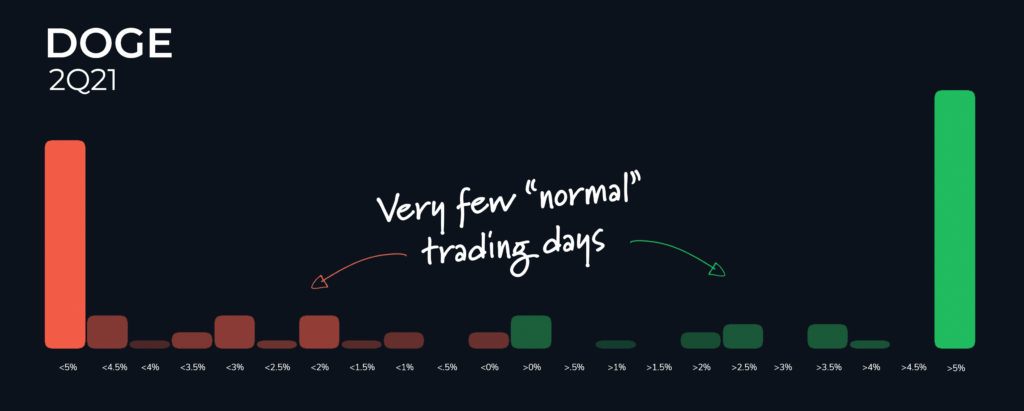

Now then, the two biggest drivers of the perfect storm of profits for Robinhood this year have been GameStop (GME) in 1Q21 and then Dogecoin (DOGE) in 2Q21. Let’s look at the pattern of the daily gains and losses for these two assets in their respective starring quarters.

To do so, we will use a histogram that shows how frequently GME and DOGE had a gain or loss of a given amount for a given day. I know that for many of us these histograms are an unfamiliar view so let me make sure that it’s clear what we’re looking at here. I promise you that it will be worth the effort.

In 1Q21 there were 60 market days for GME. Out of those 60 market days, GME was down more than 5% on 23 of them and it was up more than 5% on 14 of them. So 37 out of 60 days (i.e., over 60% of the time) GME was up or down by at least 5%.

In 2Q21 there were 91 market days for Dogecoin. (Cryptos trade 7 days a week.) On 25 of those days, DOGE was down by more than 5%, and on 31 of those days, DOGE was up by more than 5%. In other words, DOGE was up or down by at least 5% more than 60% of the time.

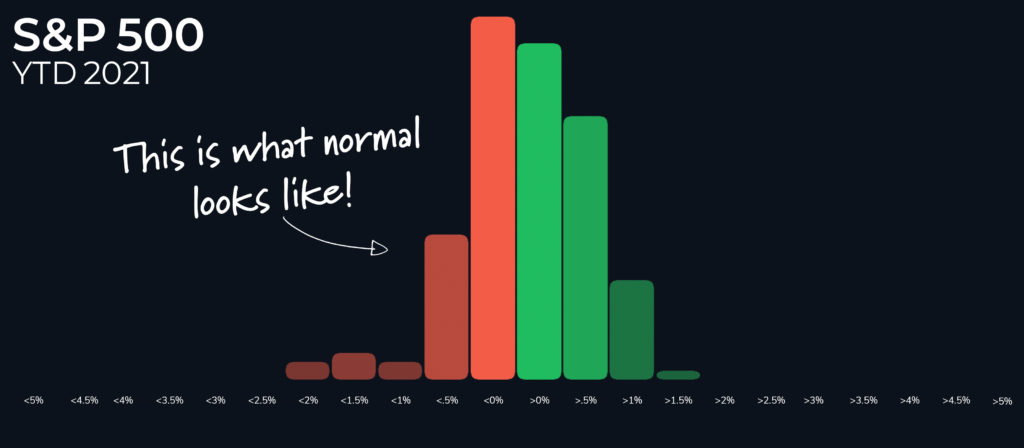

In the immortal words of farmer-philosopher Joel Salatin, “Folks, this ain’t normal!”

For an idea of what normal looks like, let’s take the S&P 500 for all of 2021. Thus far in 2021 there have been 143 market days. 110 of those days have been between -1% and +1%. In other words, over 75% of the time, the S&P 500 changed by less than 1% on any given day.

What we are seeing here is that GME in 1Q21 and DOGE in 2Q21 were extremely volatile. They almost never had “normal” returns of plus or minus 1% on any given day. They almost always had abnormal returns of plus or minus 5% on any given day!

Robinhood made a ton of money on GME and DOGE in 2021. Robinhood even had to disclose “less trading in Dogecoin” as a risk to its business in its recent pre-IPO S-1 filing with the SEC:

“A substantial portion of the recent growth in our net revenues earned from cryptocurrency transactions is attributable to transactions in Dogecoin. If demand for transactions in Dogecoin declines and is not replaced by new demand for other cryptocurrencies available for trading on our platform, our business, financial condition and results of operations could be adversely affected.”

Robinhood S-1 filing

It’s clear that these abnormal patterns of returns are the bread and butter of Robinhood’s “free” trades model. If Robinhood is to thrive going forward, there will need to be many more GME and DOGE style episodes. Why are these patterns so valuable to Robinhood and what do they mean for us as investors?

What really stands out to me is how “polarized” the patterns of gains and losses are in both GME and DOGE. Polarization is profitable for Robinhood. It leads to “activity.” It leads to “engagement.” It leads to users buying and selling these assets at distorted prices. It leads to more sophisticated (aka risk literate) market participants paying Robinhood for the privilege of arbitraging these price distortions and profiting on the inevitable reversion to the mean.

I contend that this pattern of polarization is the main pattern of profitability for online social media driven platforms. It’s stunningly easy to see when we look at it here in the context of Robinhood’s business model (thank you Robinhood!), but it’s actually the same pattern that we see over and over again in today’s consumer and media driven economy. It’s the pattern of today’s vaccine debate. It’s the pattern of political polarization. It’s a big part of the pattern of Tesla. It’s the pattern of slot machines.

These patterns of polarized returns create cognitive dissonance and a sense of urgency. They leave us confused – unable to make sense of things – and, most importantly, they leave us looking to others to give us the answers instead of trying to really think things through for ourselves.

Polarization creates the illusion of individual control while actually fostering collective control (e.g., profitability) by a centralized authority. It feels like you’re in control when you pull the handle on the slot machine but you’re not. The payouts have already been set in advance.

It feels like you’re in control when you express your strong “us against them” political views. It feels like you’re in control when you buy GME and DOGE and relish the opportunity to “take down corrupt Wall Street hedge funds.”

The unvarnished reality, however, is that the “house” is taking all of these “feelings” of control to the bank. Slot machines are the most profitable device in a casino. Robinhood made $420M in 1Q21 alone by monetizing these “feelings” of independence via transaction fees paid to Robinhood by wholesale market makers for the privilege of filling the orders of Robinhood’s users. It’s applied behavioral psychology for centralized profitability.

Is it a stretch to consider that Robinhood might have some interest in encouraging these feelings? Is it a stretch to consider that the very structure of today’s internet is set up to encourage polarization and then to monetize that polarization?

No, it’s not a stretch. This is the pattern of profitability for today’s internet. It’s the pattern that results in the public mispricing the things that we are being sold. It is the pattern of the risk-literate picking the pockets of the risk-illiterate. This is the pattern of for-profit surveillance capitalism.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that it’s within our power to say, “Thanks but no thanks!” The more that we can start to see these patterns in real time, the more that we can opt out of participating in them. The whole house of cards hinges on our consent and our participation. It hinges on keeping the real costs hidden from us to grease the wheels so that our “feelings” can run free.

What happens if we all wise up and opt out? What happens if we start to educate ourselves, think for ourselves and vote with our capital and our attention by opting out of these rigged games?

Change happens, that’s what.